Yes You Can: Why Catholics Don’t Have to Vote Republican

Gerald J. Beyer

Republicans often use overheated and oversimplified rhetoric regarding the affinity between Catholic teaching and their platform. As a result, many people mistakenly assume that a Catholic must vote Republican. David Carlin, former Democratic Rhode Island senator, seems to have fallen prey to this fallacy (“Two Cheers for John McCain,” Commonweal, May 9).

Like many other well-meaning Catholics, Carlin argues that “there is no logical way to vote for the presidential candidate of a party committed to the preservation and extension of abortion rights.” He maligns “Catholic in name only” types who resort to intellectual chicanery to justify voting for candidates who support “the slaughter of innocents.” In this context, it is interesting to ponder why so many distinguished Catholic public servants, activists, and theologians have endorsed Barack Obama, a Democrat, for the presidency.

As an institution, the Roman Catholic Church does not tell believers for whom or against whom they must vote, despite what some politicians, pundits, and pastors suggest. Rather, as the U.S. bishops write in Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship (2007), “the responsibility to make choices in political life rests with each individual in light of a properly formed conscience.”

Certainly Catholics must seriously consider any candidate’s stance on “intrinsic evils” such as abortion, racism, and torture. Catholics may not vote for a candidate who supports an intrinsic evil “if the voter’s intent is to support that position.” Yet Catholics may choose a candidate who does not unequivocally condemn an intrinsic evil for other “truly grave moral reasons.” Catholics ought to choose the candidate who is least likely to promote intrinsic evils and the most likely to promote “other authentic human goods.” So the question becomes: Are there “grave moral reasons” that permit Catholics to vote for Obama, or any other candidate, despite his or her prochoice stance, or would such a vote be “intellectually careless or downright disingenuous,” as Carlin asserts?

In the U.S. political context, where no candidate perfectly mirrors Catholic teaching on issues such as abortion, war, stem-cell research, poverty, discrimination, gay marriage, and immigration, voting should be a difficult matter of conscience for Catholics. Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship argues that these issues “are not optional concerns which can be dismissed.” While John McCain’s voting record on antiabortion legislation may be more consistent than Obama’s with Catholic teaching, he supports federal funding for embryonic stem-cell research—an intrinsic evil that Catholic teaching unambiguously condemns. He supported and promises to continue a war that the members of the Roman curia and the U.S. bishops deemed unjust. The bishops have called for a “responsible transition in Iraq...sooner rather than later.” They caution against a hasty withdrawal that would abandon U.S. legal and moral responsibilities to the people of Iraq. Yet they see continuing military operations there as a catalyst for the insurgency and unlikely to promote sustainable peace. The bishops also urge nonmilitary actions, such as diplomatic engagement with Syria, Iran, and other nations in the region that “address the underlying factors of conflict.” Is this the kind of “soft patriotism” tinged with “pacifism and cosmopolitanism” that Carlin rejects in the positions of Obama and other Democrats?

To return to the main question, what issues might weigh so heavily on the consciences of Catholics that they choose to endorse Obama? The obvious place to start is precisely the so-called war on terror and foreign policy more broadly. As is well known, Obama consistently opposed the war in Iraq and supports a timely and responsible withdrawal. In a speech in September 2007, he outlined his proposals to bring the war to an end. They include: talks with Syria, Iran, and Saudi Arabia; eschewing war with Iran; continued training of Iraqi forces; increasing aid for Iraqi refugees from $183 million to $2 billion; welcoming Iraqi refugees to the United States; a UN Iraqi war-crimes commission; and building schools throughout Iraq.

Not only is Obama’s position on the war and his strategy to end it more consonant with Catholic teaching, but his vision for the place of the United States in the international community much more closely resembles modern papal teaching on international relations. “I don’t want to just end the war,” Obama has said, “but I want to end the mindset that got us into war in the first place.” After his long conversations with Obama’s foreign-policy team, the journalist Spencer Ackerman reports that “the Obama doctrine” seeks to abandon “the politics of fear” and “spreading democracy” in favor of “dignity promotion” (“The Obama Doctrine,” American Prospect, March 24). In other words, Obama will pursue much more dialogue with other nations and attack the conditions that create misery and generate anti-American sentiment in impoverished countries. As Obama put it, we must “more effectively tackle the twin demons of extremism and hopelessness that threaten the peace of the world and the security of America.”

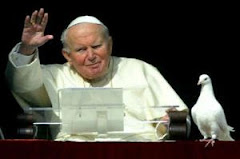

Obama ranks among the few politicians who embrace Pope Paul VI’s 1967 dictum, “development is the new name for peace.” More recently, one finds resonances between Obama’s understanding of U.S. global leadership and responsibilities and that of Pope Benedict XVI. In the pope’s address to the United Nations, he argued that the best way to eliminate inequality among nations and to increase global security is to promote human rights. Throughout his papacy, Pope John Paul II tirelessly advocated globalization that is guided by the principle of solidarity, which precludes marginalizing weaker nations. This requires creating a world community based on “mutual trust, mutual support, and sincere respect.” All nations must be equal dialogue partners, with the right to influence global decision making. Candidates who speak of “obliterating Iran” with nuclear weapons, as Sen. Hillary Clinton did, or of evicting Russia from the G-8, as McCain suggested, do not share the Catholic vision of a just internationalism guided by the principle of solidarity. Obama does. He has argued that U.S. global leadership requires much greater “investments in our common humanity.” In order to help people lead lives “marked by dignity and opportunity,” Obama proposes to double foreign aid to $50 billion by 2012, and to create a $2-billion Global Education Fund—akin to the 9/11 Commission’s recommendation.

Obama favors a robust U.S. military, judiciously deployed. He argues that the United States must restore its leadership position and protect its own security by promoting the welfare of impoverished and oppressed peoples: “We must do so not in the spirit of a patron, but in the spirit of a partner—a partner that is mindful of its own imperfections.” On his view, reaching out to other nations is not an exercise of charity, but a matter of “recognizing the inherent equality and worth of all people.” McCain, on the other hand, taunts Obama for his desire to negotiate with nations like Iran. Catholics who share recent popes’ understandings of international affairs should pray that if McCain becomes president, he does not lead the United States into a disastrous war with Iraq’s neighbor. Such an unjust “preventive” war would kill more innocent civilians. A vote for McCain breathes new life into the neoconservative foreign policy—sometimes disguised in the language of humanitarian intervention—that has wreaked havoc in Iraq during George W. Bush’s presidency. As Human Rights Watch Executive Director Ken Roth argues, the invasion of Iraq was not a humanitarian intervention because Saddam’s mass-murder of Kurds had ceased much earlier, “nor was such slaughter imminent.”

On the domestic front, Obama and the U.S. Catholic bishops believe we must more aggressively confront the enduring problem of racism. Both appreciate the progress that has been made over the past several decades. Yet, as Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua of Philadelphia has put it, the “intrinsic evil” of racism has remained “deeply rooted in American life.” In his 2001 pastoral letter Dwell in My Love, Cardinal Francis George of Chicago lamented persistent discriminatory housing patterns, devaluation and underrepresentation of minorities and their cultures, unjust judicial penalties for minorities, and the perpetuation of racist attitudes in American society. Likewise, Obama described the pernicious consequences of racism in his speeches in Philadelphia and at Howard University, and in his “Plan for Strengthening Civil Rights.” He contended that the educational achievement gap between black and white students in the United States stems from the inferior schools that many African Americans must attend. He criticized unfairly harsh penalties for first-time nonviolent offenders, which are disproportionally given to minorities. He also decried racial profiling and the attempt by the Justice Department to eliminate affirmative-action programs at U.S. colleges and universities.

Obama and bishops who have spoken out against racism propose many of the same remedies: ensuring that children of minorities and the poor have good educational opportunities; eliminating racial disparities in the justice system; and fair access to credit and housing for minorities. Obama’s ability to enter into dialogue with people of different ideological stripes and his profound understanding of racial injustice allow him to address racism in a way that McCain cannot. Obama alone has spoken passionately and persuasively on the issue and has a proven track record both as a community organizer among the disenfranchised and as a civil-rights attorney.

he U.S. bishops and recent popes have advocated a more just economic system in the United States. The late Pope John Paul II, for example, decried America’s neoliberal capitalism, which “considers profit and the law of the market as its only parameters” and fails to protect the weakest members of society. The U.S. bishops support policies including a living wage, affordable health care, welfare reform, and fair taxation. Obama opposes the “sink or swim” capitalism that has created unjust economic disparities in the United States. Yet Obama, like Pope John Paul II and the bishops, recognizes the potential of the market economy, guided by reasonable and just social policies, to advance the welfare of all members of society.

By contrast, John McCain professes faith in the unfettered forces of the market. He proposes little to advance the cause of health care for all or to end the mortgage crisis, and he supports tax cuts for the rich and for corporations. He embraces the “trickle down” economics that favors the accumulation of wealth by some at the expense of the many. Anyone vaguely familiar with the church’s social doctrine since Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum novarum (1891) knows that Catholic teaching eschews laissez-faire capitalism, which Republicans have religiously avowed since the Reagan revolution (though they have not always practiced it, as evidenced by Bush’s hefty farm subsidies). As Angus Sibley recently noted in these pages, John Paul II’s Centesimus annus insisted that “there are collective and qualitative needs that cannot be satisfied by market mechanisms” (“The Cult of Capitalism,” April 25). “We Catholics should not be shy about what distinguishes our recipe for the good society from that of libertarian theorists,” Sibley argued.

Of course, economic policy issues are matters of prudential judgment, which means Catholics may disagree on specific measures. It is difficult, however, to maintain that McCain will better adopt the church’s teaching on the preferential option for the poor, which is, to borrow a term from Catholic conservatives, non-negotiable. Catholic teaching holds that the justice of an economy and any particular policy must be measured by how it affects the most vulnerable. Since President Bush took office in 2000, 5.6 million more Americans have fallen into poverty. The administration’s slashing of antipoverty programs does not augur well for our nation’s poor, given that McCain would likely maintain the status quo. Yes, McCain has promised to make poverty a “top priority,” but actions speak louder than words. On several occasions McCain voted against minimum-wage increases and has never been on the front lines of the war on poverty. Obama has. From his efforts to empower the poor of Chicago’s Southside in his early adulthood to his recent cosponsoring of the Global Poverty Act, Obama has exhibited the will and know-how to fight poverty. His plans to tackle poverty share the Catholic emphasis on social change coming from the ground up. Recently Obama pledged to work with former Sen. John Edwards to halve domestic poverty in ten years. This plan, available on the Center for American Progress Web site (www.americanprogress.org), contains detailed proposals, not empty platitudes.

Perhaps the most important commonality between Catholic teaching and Obama’s proposals is one of philosophical orientation. Both stress the necessity of nurturing the virtue of hope. The Catholic tradition holds that without hope in one another there can be no justice, no spirit of solidarity among human beings. Without hope in one another, social trust disintegrates and dialogue breaks down. When that happens, we resolve to take care of our own interests. We take advantage of, or at least ignore, the downtrodden and the marginalized. Like Barack Obama, Catholicism embraces the language of hope and solidarity, without which change for the sake of peace and justice for all cannot occur. Naysayers who consider the language of hope utopian, impractical, or “soft” ought to take note of successful movements like Solidarnosc in Poland during the 1980s, which was imbued with the spirit of the Catholic tradition and the language of hope. It is no coincidence that Lech Wałesa, the audacious electrician and leader of the Solidarity movement, titled his autobiography A Way of Hope.

Like David Carlin, many Catholics rightly oppose Sen. Obama’s prochoice position, which contradicts Catholic teaching. Still, they ought to consider his promise to reduce the number of abortions by fostering socioeconomic conditions that favor choosing life and by promoting abstinence as a way of reducing unintended pregnancies. They should also contemplate the fact that Republican presidents have not done a better job of reducing the number of abortions, as Daniel Finn has pointed out (“Hello, Catholics,” Commonweal, November 4, 2005). According to Finn, Republicans like Bush have championed the abortion issue without exerting much energy to eliminate current abortion practice. That may not satisfy the conscience of some Catholics; they may decide to vote against Obama. Still, such a choice must be made after sincerely attempting to discern which candidate will more fully advance values and policies akin to the Catholic vision of solidarity, social justice, and the common good. As the USCCB has taught, Catholics must examine a candidate’s stance on the full range of issues that ought to weigh on a Catholic’s conscience. Undoubtedly, many Catholics who support Obama have done just that. Catholics who endorse him should strongly encourage him to take steps to limit the evil of abortion. Finally, during this election season Catholic voters should not be duped into believing that the matter is already perfectly clear: Vote for McCain or be a bad Catholic! They ought to take their obligation to vote according to their consciences more seriously than that.

Gerald J. Beyer is assistant professor of theology at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia.